In Senegal, you learn by doing

Many young Senegalese get their education bìin a company, in practical work: if you want to fish, go out to sea - the experience comes naturally. But most of the work is informal, with low wages and no security. The union now wants to create more opportunities for the youth, with exams and diplomas. A report.

With a mixture of embarrassment and pride, Abdul Khadre rubs his upper arm. Without saying anything, he tightens it ever so slightly - a sizable muscle ball emerges from beneath his Portuguese soccer shirt.

He is standing on the quay in the port of Rufisque, a suburb of Dakar, where today's spoils are being brought in.

The last praus are sailing in, the traditional wooden boats that Senegalese fishermen use to take to the sea to catch sardinella for thieboudiene, the national dish of rice and fish. For Abdul Khadre, the day is over; the work is now up to the boys who bring the fish ashore. Balancing with dripping crates on their heads, they trudge back and forth from boat to wharf. On the asphalt, the catch is poured out for the ready buyers.

Besides sardinella, there are sardines and dorades; a cart full of swordfish drives by. It is a gray Sunday afternoon - favorable for the catch, says Abdul Khadre, then the fish swim closer under the surface. He has worked in fishing here for years, he knows no different, just look at those strong arms. Like the other boys from town, he used to come here every day as a child. Then they would pick up the fallen fish from the beach to sell. Now he goes along on the boat to catch them himself.

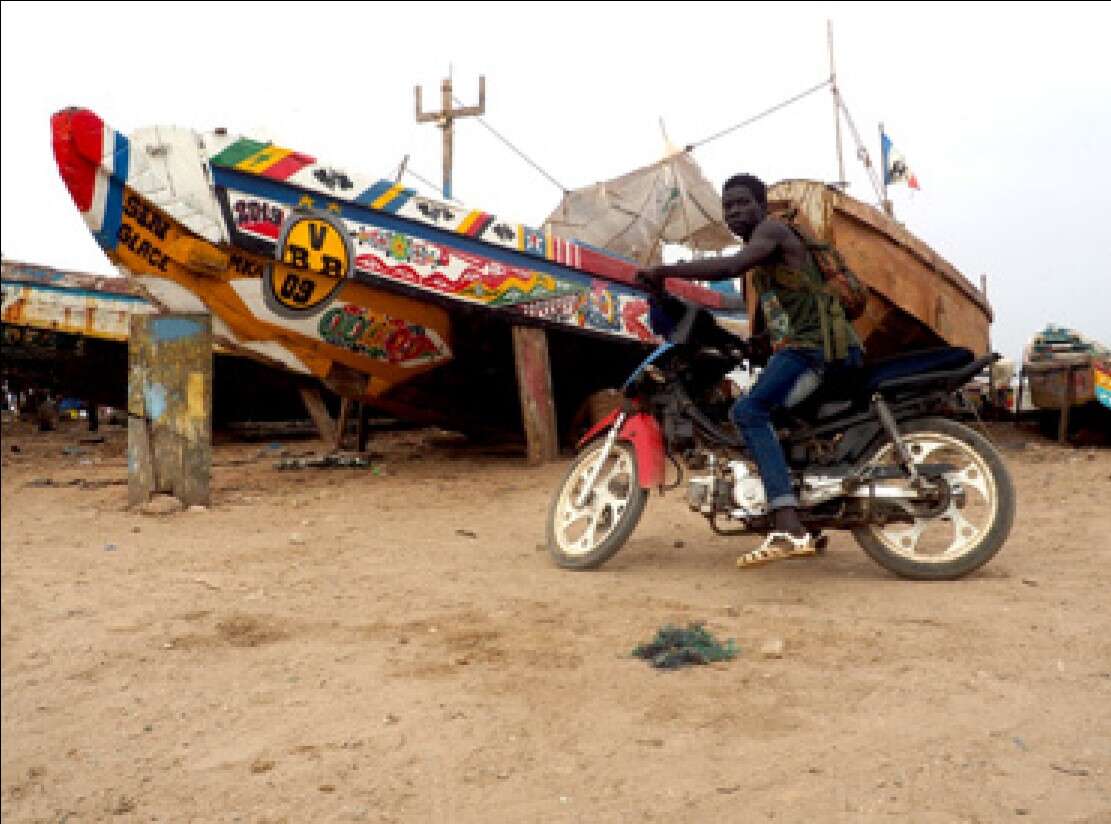

A young man leaves the harbor - the colored praus are ashore, the working day is over.

Day labor is the Earning you do per day, the trade you learn at sea. With no employment contract, no training or diploma. Without security.

Being able to sail along is a matter of being on shore early in the morning. So it goes for many people working at the port - from the "transporters" who bring in the cargo, the girls who sell bags of salt to preserve the fish, the women who clean or grind the fish into mince on the spot - most of the jobs here are informal.

It is estimated that fishing employs seventeen percent of the labor force - although the figures vary, as informal work is difficult to capture in statistics. Fishing is by no means an exception: according to a 2018 World Bank report, nine out of ten workers work in the informal economy.

Superficially , Senegal seems to be doing well economically. For years the economy has been growing at over six percent and the outlook is good. Starting in 2022, growth rates would become even rosier, thanks to the anticipated offshore extraction of oil and gas.

Still, poverty and inequality are persistent in the West African country. According to the World Bank, this is largely due to the weak labor market; the labor force is growing faster than the number of jobs. Among young people, unemployment stands at nine percent, compared to six percent overall. Moreover, nearly two-thirds of young people are inactive, a relatively high figure. And for those who have work, it is often informal, under fragile conditions, low wages and almost no social protection.

Finding a "real job" before the age of thirty-five is rare here.

As such, over two-thirds of working young people between the ages of 15 and 35 live in poverty. To provide prospects for the rapidly growing young population, employment and decent jobs are crucial. But private sector employers in particular complain that the gap between the skills they demand and those young people can provide is too wide. And Senegalese education only barely prepares them for the job market.

How can you ensure that young people's skills are better matched to the labor market? And how do you move young people from informal to formal work? A tour of government, unions, employers and young people themselves.

Pikine, stuck on the east side of Dakar, is often called a suburb of the capital, but with more than a million inhabitants, it is officially Senegal's second city. It is a place that has visibly exploded into a city; dirt roads lead through packed blocks of houses, the walls unpainted and drab, the many stores improvised from rags of cloth and wooden poles.

Many of the Senegalese who flee the countryside in search of work in the capital end up here. The union UDTS (Union Démocratique des Travailleurs du Sénégal) is also based here. This local union works with the Dutch trade union CNV Internationaal on the employability of young people, including by actively involving them in policies that affect them.

At the union, their voice was given a permanent place with a special youth committee, the Comité National des Jeunes de l'UDTS (CNJ).

Trade union training for young people

Through CNV Internationaal the youth receive negotiation and lobbying training, which focuses on the CNV method of social dialogue: instead of striking and standing up for rights in confrontation with the government, the focus is on consultation. By looking for common interests you are more likely to reach sustainable solutions, is the idea.

Today the CNJ is meeting in Pikine on youth employability. 'A ticking time bomb,' says chairman Malick Sow in a soft voice. 'More than half of Senegalese are under 30 and every year two hundred thousand more young people enter the labor market. That's an immense challenge.'

Sow himself has an IT consulting business, which he set up after a two-year study with help from the union. 'At UDTS I received training in entrepreneurship, human resources and labor law - skills you don't acquire at school. This allowed me to get started myself, rather than wait and see.'

Official jobs are few and far between, and if they exist, young people often don't qualify, says Sow. 'Companies always ask for at least a few years of experience, but where are we supposed to get that?' A round of introductions to the youth committee members makes the answer clear: Each of them tells how they paired internship to training to internship before ending up at their current jobs. Three of the seven young people - most of whom are approaching 30 - work in the formal sector. "A lucky thing," says Sow, "because finding a "real job" before the age of thirty-five is rare here

Nurse Khady Diakhaté is a member of the youth committee of union UDTS.

A stroke of luck, yes - 'but it didn't just happen to me,' says Khady Diakhaté, dressed in blue nurse's uniform with matching headscarf. 'During my training as a nurse, internship was a regular part of the program, but I didn't manage to find a paid job after I graduated.'

The public hospital in Dakar first asked her for a three-month internship, then she was offered two more three-month internships. "I took it," she says, "hoping to get a spot that way.

"After nine months of unpaid internship, I stayed away for two months; I couldn't make it anymore. The union then started negotiating with my boss. Now I am finally working under contract."

Nurse Khady Diakhaté

That employers first ask for internships is not surprising to the young people - it is a well-known problem that Senegalese education often does not match what is required in the workplace. Courses tend to be general and not vocationally oriented. At the very least, an internship gives young people the opportunity to gain the requested experience.

Union negotiates internships

Trade union UDTS is therefore also negotiating the creation of internships in the collective bargaining process. 'But the fact that sometimes nothing is paid for these internships is not fair and not tenable,' says foreman Sow. 'We are urging the government to abolish unpaid internships. She agrees with us on principle, but we're not there yet.'

'Our youth, energetic and creative, embody Senegal's hope and strength. They will remain at the forefront,' President Macky Sall promised at his re-election in February. 'We will invest even more in youth employment and employability.' It is a promise with which he managed to defeat incumbent President Abdoulaye Wade in 2012, who 12 years earlier, as "president of youth," had still received the massive vote of young Senegalese. But what had Wade - who was well past 80 - done for them?

With that question, the youth of Y'en a Marre ("we are fed up") shook up Senegal. The movement of journalists and rappers urged the youth to raise political awareness with music and protest rallies. It led to mass demonstrations leading up to the presidential election.

This was striking for the country always praised for its stability. Senegal is the only country in West Africa that has not seen a coup or civil war since independence. Finally, Wade had to give way to Macky Sall, who won the election.

The youth of UDTS seem to be patient with their current president. The union's youth committee is also part of the National Youth Council, which represents young people in talks with the government and civil society organizations about youth policy. 'We have good discussions with the government,' Sow said. 'Of course there is a lot of work to do, but not everything is in the president's hands.

Hands-on training

For us, it is important that the government recognizes that youth employability is an essential issue - and it is doing so An example of successful negotiations between unions, government and employers is the École-Entreprise program, launched last year by the president as part of his strategy for an "emerging Senegal. Over three years, 25,000 young people are to be placed in this hands-on training program.

'In Senegal, this is the first training based on the Swiss model,' Mbaye Sarr proudly presents. He is the chairman of the vocational training committee of employers' association CNES and saw firsthand how young people in Switzerland are largely trained on the job.

Ragingly, he is enthusiastic about the dual model. 'Young people learn what a company needs from them and the training seamlessly connects with the labor market. They are also immediately introduced to the corporate culture.'

He cites the training of 24 young people at the five-star Terrou Bi hotel on the coast in Dakar, who received in-house training in the hospitality industry as a pilot. It greatly increased the participants' job prospects, says Sarr. 'Nineteen of them now have a job - some at the hotel itself, the rest have found work elsewhere thanks to help from the boss.'

From the age of 16, École-Entreprise allows you to choose between various sectors, from hospitality and tourism to energy, agriculture, transportation and electromechanics. The Ministry of Work, Vocational Training and Crafts pairs the young people with companies. 'Ten thousand places are already available,' says Michel Faye, the coordinator on behalf of the ministry. 'It is up to us to bind as many companies as possible to our plan in the coming years.'

One of the few women working around the slaughterhouse turns sausages from mutton

In doing so, Mbaye Sarr has to help him on behalf of the employers. 'The first year the government pays forty thousand CFA francs,' he says. In other words, sixty euros, compared to the Senegalese minimum wage of ninety euros a month for full-time work. 'The second year the contribution halves and the company supplements the twenty thousand. The last year that ratio is ten thousand versus thirty thousand francs.'

A good deal for everyone, he thinks: 'After three years, the student has a diploma worth more than with a theoretical education, and the employer has a well-trained employee who is formed to the company's own.'

Actually, it's nothing new, says Abou Sy of union UDTS, standing in the middle of the Dakar slaughterhouse, surrounded by half-cow carcasses hanging ready to be dismembered. He now works mainly as treasurer at UDTS, but started his working life here.

'We've been doing on-the-job training for years,' he says. 'The only difference is that here you don't graduate with a degree.' Abou Sy ended up here after training as a geography teacher.

Unable to find a job, he learned to make a living as a kind of meat broker, buying up sheep and goats in his neighborhood to bring them here and slaughter them. The meat he sold on. 'An academic in butchery,' he chuckles. 'But book knowledge won't get you very far here. In Senegal there is no official training as a butcher anyway. You learn the trade here, in the slaughterhouse.'

At the Dakar slaughterhouse, informal and formal work intermingle.

The dividing line between the informal and formal sectors runs across the grounds here. At the back of the slaughterhouse, men drive - informally - a seemingly endless row of cattle toward their fate. One by one, the men secure them in the rack, slit their throats and place the wetting body on the pile, which will soon pass the staff on the cable car and be eviscerated; formal work, by certified workers employed by the slaughterhouse.

Further down the sales hall, a boy stands busily negotiating with a family over a piece of meat. 'Khadim,' he introduces himself. He, too, deals in meat. Five cattle he has brought with him today.

'Not a top price,' he says, 'sometimes I come to ten head.' But it's not a bad deal: the refrigerator is broken. 'We are in negotiations with the slaughterhouse about repair, but the question is who will pay for it...' It's one of the disadvantages of informal work, he admits. But what choice does he have? Without papers, there is hardly any alternative. 'That's something where the union can help,' says Abou Sy of UDTS.

Although he still comes here from time to time as a meat broker, his union work is taking on an increasingly important role.

'Our key word is: formalize. Guys like Khadim have the skills, but not the formal recognition of them through a diploma. That makes them vulnerable.' For example, without a diploma, Khadim does not have the opportunity to apply as a butcher for a formal job at a restaurant - with more social rights and livelihood security.

'With exams and certificates, you make these young people more independent,' Sy says. 'Then they can charge a higher price or apply for a permanent job, where salaries are up to three times higher.' It forms one of the spearheads of lobbying the government. Meanwhile, Abou Sy especially urges young people to organize. "If they make themselves heard together, the bosses here will be more willing to listen to them

Diamaguene sewing workshop trains girls without an elementary school diploma in the trade

The sewing workshop of three couturiers in the Diamaguène neighborhood of Pikine shows how certifying young people's skills can increase their opportunities. the three friends Bada Mbaye, Ameth Guisse, and Moussa Fall saw how girls in their neighborhood in particular struggled with lack of future prospects. Many of them dropped out of elementary school due to lack of money or difficulty keeping up.

They decided outside their own business to open a sewing workshop where girls and young women could learn the trade. They themselves teach there voluntarily; the girls pay five thousand francs a month. Currently, 140 girls between the ages of thirteen and 35 are training here.

It is hard work; one classroom is available per year and a total of about ten sewing machines can be distributed. They are classic, black vintage Singer machines, "a donation from the American Embassy," says Guisse. The studio depends on donations of fabric and other materials, so making a multi-year plan is out of the question. Progress comes in small steps.

Recently, the government decided to officially certify their training - the girls now receive a real diploma, and it is paying off. Proudly, Mbaye hands over a contract from one of their former students: she now works for the army, adjusting soldiers' costumes.

Traditional Senegalese clothing: final exam assignment at sewing school

It is a rare example of a girl without an elementary school diploma managing to find her way into formal work anyway, thanks to the efforts of three committed local entrepreneurs. From internships to vocational training and from certifying informal work to opening up a range of funds to small business owners - increasing youth employability is a multitude of initiatives, each with its own small target audience.

The World Bank is critical of this. A Youth Employment Agency was created in 2014 to bring more unity and coherence to fragmented policies, which were also spread across a variety of institutions and ministries.

The creation of the ANPEJ (Agence Nationale pour la Promotion de l'Emploi des Jeunes) is a fine first step, but coherence remains a challenge, the World Bank judges in a late 2018 evaluation report. In addition, funds fall short. More so, the World Bank highlights the problem that current policies mostly favor the upper class. For example, vocational technical education - which has been in vogue in recent years - significantly improves young people's job prospects, but only 7.7 percent of young people who complete primary education have access.

The system serves the well-educated young men from the city, the focus is mainly on policies for the formal sector. Isn't that strange, considering that less than 10 percent work in the formal sector? Most people learn work skills within the family and by doing in the informal sector. That presents opportunities, the World Bank believes, if you can certify competencies - which is hardly the case yet. 'The synergy between the programs is lacking,' UDTS union members admit.

But there is no room for real pessimism - not with them, but neither with the ministry and employers. What matters, they say, is that Senegal is on the move. 'This is the best thing we can do for young people,' says Mbaye Sarr of the employers' association

At the port of Rufisque, the day is drawing to a close, people dragging the unloaded praus toward the beach. They are the same brightly colored boats that several thousand Senegalese youths used to cross to Europe - and in which hundreds died. Senegal is one of the most common countries of origin of migrants heading west from Sub-Saharan Africa.

The money they send home plays an increasing role in Senegal's economy. As recently as 1990, remittances amounted to $142 million; by 2017, that figure had exploded to more than $2 billion - about 10 percent of GDP. Whether the creation of more jobs in Senegal can change that is very much in doubt, according to most Senegalese; rather the opposite. 'Migration is not for the poor,' they say -those who want to cross with the help of smugglers must pay handsomely.

For Abdul Khadre, one thing is certain: his future is here. Between the sea and the port of Rufisque.

Text and photos Eline Huisman, published in Vice Versa, September 2019

(Fishing photos: Bas de Meijer)

Publication date 25 03 2022